This course examines computation through the histories, cultures, and techniques of measuring and drawing in architecture. Its dual goal is to introduce students to the technical fundamentals of computation while also challenging common aesthetic assumptions—treating computation not as a shortcut to complexity or precision, but as a conceptual framework for design inquiry.

Classes will meet in the Center for Collaborative Arts and Media (CCAM)Links to an external site., working primarily in the Leeds Studio, which houses CCAM’s Motion Capture (MoCap) research environment. Students will work with Processing, Vicon Tracker, and a range of sensing tools—microphones, cameras, and other real-time measurement devices. Together, these platforms will form the basis for building frameworks that translate MoCap and sensor data into interactive sketches, revealing new ways the digital and physical can intersect and influence one another.

The course will start with an introduction to coding through Processing and a brief history of computational design through early rule-based art. Students will recreate these early generative exercises using the CCAM MoCap system, connecting historical precedents with contemporary sensing technologies. The second half of the semester will begin with students presenting proposals for research-based projects that culminate in a live sensor-based drawing using the workflow(s) developed in the first half of the semester. Through a series of iterative workshops, students will refine their proposals, develop custom workflows, and ultimately produce proof-of-concept projects demonstrating computation as a tool for architectural thought and experimentation.

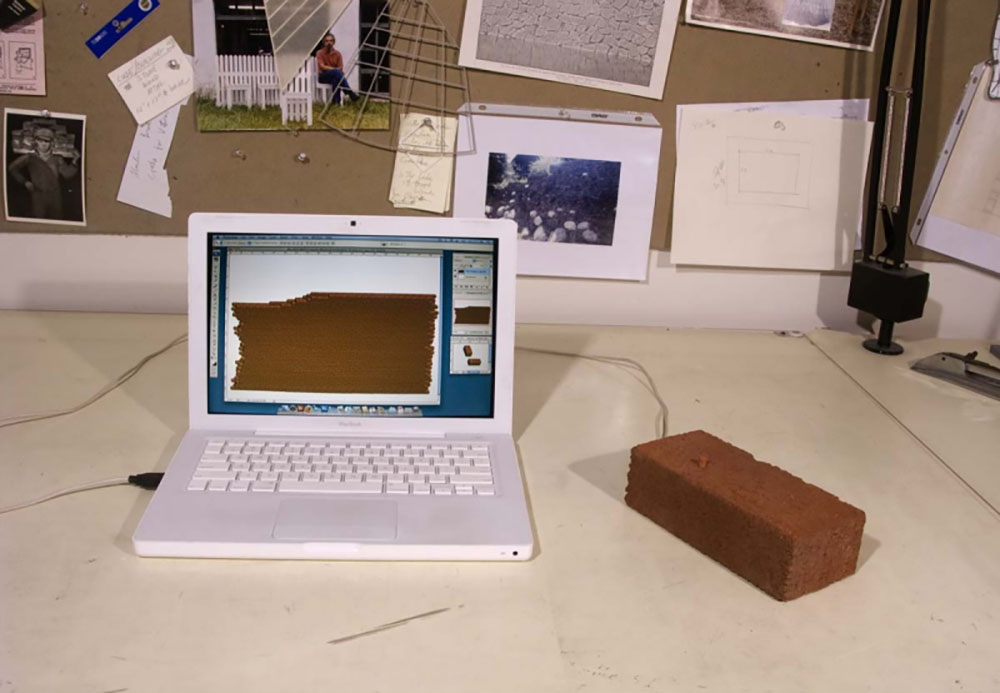

How to Build a Digital Brick Wall – Allan Wexler, 2009

Computation is, at its core, the execution of mathematical operations. In this regard, computers excel at two things:

- performing complex calculations almost instantaneously, and

- repeating those calculations endlessly without error.

These are precisely the tasks that humans—and the physical world—tend to perform poorly or inconsistently. Yet, while computers are inherently discrete, humans are inherently idiosyncratic. Our actions, bodies, and the environments we occupy introduce noise, variation, and unpredictability into systems that are otherwise formally rigid.

Rather than position these differences as shortcomings to be overcome, this course leverages the tension between discrete computation and the messy realities of physical experience. It uses this contrast as a critical lens through which to understand what computation is and what it can do.

Wall Drawing Instructions – Sol Lewitt 1971 Drawing Restraint 2 – Matthew Barney 1988

Drawing as the Analog to Computation in Architecture

In the discipline of architecture, drawing has long served as the analog counterpart to computational thinking. Alberti’s De pictura presents one of the earliest mathematical solutions to the problem of constructing a perspectival tiled floor—a process that formalizes drawing as a geometric calculation. A century later, architects and engineers expanded this approach through the development of descriptive geometry: techniques for producing precise planar projections of three-dimensional objects and spaces.

These methods remain fundamental today, even if vellum has largely been replaced by digital interfaces. Modern design software performs these geometric constructions continuously in the background. Although the results appear as intuitive manipulations of three-dimensional forms, what we are actually seeing is a series of real-time, computationally constructed drawings.

Whether we construct a drawing by hand, or it is done in the background by software, what we represent or see is the interpolation of points and their connections (as edges) in three-dimensional space. Through an understanding and discrete control of this interpolation we can introduce new mechanisms to control or input the construction of drawings. Opportunities emerge to replace a pencil or mouse with a brick, sound, wind, insects, the human body, etc. Rather than think of a drawing as a deterministic representation where fidelity or a visual analog. is the goal, drawing can be thought of as an open-ended process (similar to Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings) where the outcomes are endless.

Debug – Edhv, 2010

Interpolation, Inputs, and New Mechanisms for Drawing

Whether produced by hand or through software, any drawing is ultimately an interpolation of points and their relationships—edges, vectors, surfaces—in three-dimensional space. When we gain discrete control over this interpolation, we open the possibility of redefining what counts as an input.

In this expanded framework, a drawing tool need not be a pencil or mouse. It can be a brick, a gust of wind, a human gesture, a swarm of insects, a microphone, or the rhythm of footsteps. These inputs can drive the construction of form just as rules drive Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings: not as deterministic representations where fidelity is the goal, but as open-ended systems capable of generating endless outcomes.

Measure as a Generative Tool

Measurement is inseparable from drawing, typically describing linear distances through a hierarchy of units and subdivisions. Traditional instruments—tapes, levels, theodolites—produce measures that map cleanly onto geometric construction. But when we introduce transdisciplinary forms of measurement, the relationship becomes more speculative, and therefore more generative.

Some measures translate directly. The RGB values of an image, for example, can be used as X, Y, and Z coordinates in space. Others require interpretive transformation: speed, temperature, pressure, touch, or sound must be mapped creatively into the logics of descriptive geometry. A depth camera might record the rippling surface of a sheet in the wind, which could then be used to construct a non-planar section through a virtual sphere.

In all these cases, measurement becomes more than a means of describing existing geometry—it becomes a mechanism for producing new forms of drawing, and new relationships between the physical and digital worlds.

Lunar Surface – Kimchi and Chips, 2014

Methods & Techniques:

The class will focus on a quick introduction to Processing through a series of assignments for the first third of the semester. Through Processing students will be exposed to basic programming and how data can be passed between software and various inputs. Students will then be introduced to the Vicon tracking system. The final project will be a research-based live drawing prototype or proof of concept. The interface with their project and the physical world will be with the Vicon tracking system and/or another sensor. The semester will culminate in a presentation of the students live drawing projects. Students can work individually or in pairs to develop the assignments.

Assignments:

This course will be a research-based technical seminar. Students will be exposed to the use of scripting and coding within various workflows to customize interactions and outcomes. The deliverables will be broken into exercises and a final project. The first set of exercises are meant to be built upon starting with a rule based generative sketch and then implementing readily available inputs (both live and pre-loaded) from sound to images to camera input.

Exercise 1: Rule Based Sketch– using an artist’s work or process as inspiration create a rule based generative sketch.

Exercise 2: Tracking Object – students will create physical object that can control their previous sketch using the Vicon Tracking System in CCAM

Exercise 3: Tracking Sketch – using their tracking objects students will develop a new interactive sketch.

Exercise 4: (Midterm presentation): Tracking + Sketch – students will present a final revision of their tracking objects and corresponding sketch with the introduction of another input.

Final Project – a student driven proof of concept that explores links between physical and digital spaces through creative systems of measure, sensing, and “drawing.” Students can work in pairs or as individuals for the final project.

Deliverables:

Project proposal 3/26: PDF of sketches, references, etc.

Final proof of concept 5/7: PDF, video, and perfomance of the final project as well as the development and tests.

Schedule:

Week 2 1/14 Introduction to Processing

Exercise 1: Rule Based Sketch

Week 2 1/21 Introduction to Vicon Tracker

Exercise 2: Tracking Object

Week 3 1/28 Introduction to Processing+Vicon Tracker

Exercise 3: Tracking Sketch

Week 4 2/4 Sound Input

Exercise 4: Tracking + Sketch

Week 5 2/11 ***Travel Week***

2/16 Seminar Make Up Day

Week 6 2/18 Camera Input

Week 7 2/25 Exercise 1,2,3,4: Students present a curated compilation of the three first exercises.

Final Project assigned: Final project proposal.

Week 8 3/4 Studio Midterm Week (No Class)

Week 9 3/11 **** No Class Spring Recess****

Week 10 3/18 **** No Class Spring Recess****

Week 11 3/25 Final Project proposals: Students present their final project proposals.

Week 12 4/1 Introduction to Arduino

Week 13 4/8 Class workshop

Week 14 4/15 Class workshop

Week 15 4/22 Class workshop

Week 16 4/29 **** No Class Studio Reviews****

Week 17 5/6 TBD Final Presentation